On April 13th, 1970, an oxygen tank blew up aboard the Apollo 13 spacecraft.

This caused a quadruple system failure--something the astronauts hadn't been trained to handle because it was assumed that if four systems failed at once 200,000 miles from Earth, it would be impossible for them to survive. But on their doomed lunar mission, that is exactly what happened. The astronauts and ground crew had to find creative solutions to problems no one had anticipated.

|

| This is not where you want to be when everything around you starts to break. |

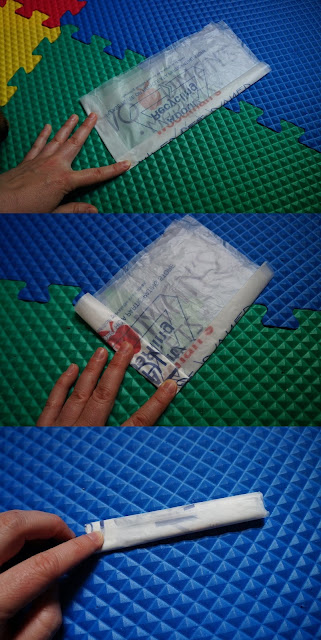

At one particularly dramatic moment in the

Apollo 13 movie, the engineers on the ground are given the instructions, "We need to make THIS fit into THIS using nothing but THIS." The actor then dramatically dumps a box of junk onto the table, and everyone gets to work. (I'm paraphrasing, the actual quote from the movie is

here.)

They needed to make round lithium hydroxide canisters fit into holes designed for square canisters using only what they had with them in the spacecraft. You can read all the gritty details

here, but for now just understand that if they could not do this, three people were going to die of carbon dioxide poisoning.

This was one of several engineering problems they had to solve to get the astronauts home safely. The academic solution would have been easy. Just design and manufacture an airtight seal of the appropriate dimensions and place it over the hole. Of course, that wasn't an option for the crew of Apollo 13.

That is the quintessential engineering problem--making something work despite far less than ideal conditions. But even though we usually think of engineering problems in terms of technology, it's often useful to apply the same thinking to other problems.

|

| Apollo 13 liftoff. It was a marvel of engineering to even get this far. |

My broad use of the terms "engineering problem" and "academic problem" come from

The Last Lecture by

Randy Pausch, (which is excellent

reading or

watching, by the way), where he explains raising his kids after being diagnosed with terminal cancer. His professional background was split between academics and engineering, so those were the two ways that he knew how to solve problems. He said that if he approached raising his kids as an academic problem, he would certainly fail. He would objectively be a terrible parent because he would disappear from their lives at a young age. But by approaching it like an engineering problem, knowing that he won't be there for most of their lives, how can he plan for it and give his family as much as possible for the future before he disappeared?

I find this thinking to be very valuable because most problems are engineering problems, but very often people approach them like academic problems.

One example that comes to mind is when a coworker complaining to me about one of our bosses. He had a laundry list of faults about how this boss was terrible at his job and bad for the company, but there was no one higher up in the company willing to take any action against him. My coworker complained to me that

he should not behave this way. And he was right, no one in that role should behave that way. But oxygen tanks shouldn't explode, and fathers shouldn't die when their children are young. Sometimes you have to deal with things that should not be, and build a solution under less than ideal circumstances. My coworker and I had to make a round peg of a boss fit into a square hole of a company using nothing but the tools and skills at our disposal, because it was an engineering problem. Was it fair? Of course not. But neither are quadruple system failures or pancreatic cancer.

|

| Most workplace problems are engineering problems. |

Once you start classifying problems as either academic or engineering, they become a lot easier to solve. In my case, I started seeing engineering problems everywhere. Difficult training partner? Engineering problem. Opening a school on a shoestring budget? Engineering problem. Siblings not getting along while I'm teaching? Engineering problem. Scheduling issues? Budget issues? Personnel issues? Engineering problems. As an added benefit, once you start looking at your engineering problem in terms of the tools you have to solve it, it becomes less of a problem and more of a puzzle.

Applying this thinking to your training can help you improve more efficiently. The first time I encountered this, it was before I had ever considered academic problems or engineering problems. I was a high school student on a volleyball team.

There were a couple star players on the team, but most of us were beginners and our coach had to teach us all the basic skills. At one practice she showed us how to dig for a ball that had gone flying off away from the intended target. It was difficult--dive after the ball, propel yourself along the ground with your free arm, let the ball bounce off your hand instead of the ground--for the small chance that someone else would be able to rush in and return the ball over the net before it hit the floor. Long before we felt comfortable with the skill, we stopped working on it.

Our coach explained that she was only introducing us to the skill, that she didn't want us to get good at it. She said that at our level, our practice time was far better spent on core skills, learning our basics well enough to prevent the ball from flying off unpredictably in the first place.

It made sense. We were (mostly) novice volleyball players with a limited amount of practice time. Approaching it as an academic problem, we would have been doomed to failure--objectively unskilled players at the end of the season. We could certainly get better as the season progressed, but it was not realistic for us to master every single skill. But our coach approached it as an engineering problem (although I doubt if she would have called it that) and looked for how to make the team as successful as possible using only the players, tools and time available to her.

Martial arts training is also an engineering problem. Real life violence is infinitely more complex than a volleyball game. Even dedicated students seldom practice, say, five hours per week. But even with that much training, it is not possible to master every single skill that might be useful in a violent encounter.

Here is a very incomplete list of potentially useful skills:

- the punching skills of professional boxer

- the kicking skills of a taekwondo Olympian

- the throwing skills of a judo master

- an equivalent mastery in every weapon, improvised weapon and firearm

- an equivalent mastery in awareness and de-escalation skills

- an equivalent mastery in active shooter and bomb threat situations

- an equivalent mastery in crowd psychology

That is the academic solution--to prepare for everything you might need. But it's not possible. Even if you did not sleep, there would not be enough hours in the day to attain all of those skills to that high of a level.

|

| Training doesn't look like an engineering problem, but it is. |

So how do we look at this like an engineering problem instead?

1. Define the goal.

If you are training to win a judo tournament, you can probably skip all that boxing stuff. If you're training purely for self defense, there's a lot of footwork and complex kicking that a high level taekwondo athlete would need but you can safely ignore. If you're trying to pass your next belt test, you can put other skills on the back burner while you focus on promotion requirements. Being clear and honest with yourself about what the goal is should help a lot.

2. Prioritize what is common.

If you've got a tournament coming up, maybe it's legal to throw a kick to the head in the middle of a double back flip, but you are far more likely to face a garden variety roundhouse kick. So practice defending and countering a roundhouse kick. Depending on the rules of the tournament, roundhouse kicks are usually more common than other types of kicks. Punches are usually more common than ridgehands.

Self defense training, in my opinion, is where this goes wrong most often. It's easy for us as martial artists to fall into the trap of thinking that certain techniques are widely taught, so we stand a reasonable chance of facing them in real situations. The fact remains that no matter how widely an arm bar is taught, we are far more likely to face a push or a punch than an arm bar.

3. Prioritize based on the progression of the event.

Just like when I was playing volleyball, there are decisions to be made about how much time to train for preventing a bad situation and how much time to spend on recovering from that bad situation.

This is going to make some people mad, but it's true. If your goal is self defense (again, see #1), you are better off prioritizing preventing bad things from happening. Prevent going to the ground by learning to end the fight before it goes there. Prevent getting in a physical altercation by learning to de-escalate. Prevent needing to de-escalate by avoiding a situation before it has the chance to turn tense.

Not getting into a fight is a skill! It might not be as fun to work on (Is your goal to have fun? Nothing wrong with that!), but if you are training because you are truly concerned for your safety, this is where you need to spend the bulk of your time. Don't ignore your physical skills of course, but your training time is better spent learning how to not need your physical skills.

4. Work on principles.

You can train more efficiently by working on principles rather than techniques. If you understand what you can do when an arm is extended toward you, it will matter a lot less whether the person is trying to punch you, push you, grab you, and so on. If you deeply understand how a hinge joint works, you can exploit its limitations whether you are manipulating someone's arm, leg, finger, or toe. It is a more difficult way to teach and learn, but ultimately it is more efficient than trying to ingrain a myriad of specific techniques to handle different but similar situations. That's the academic solution--to know the exact answer to the exact situation. Violence is just too complex to learn that many techniques.